BY COLONEL ALEXANDER K. McCLURE.

While Lincoln would have been great among the greatest of the land as a statesman and politician if like Washington, Jefferson and Jackson, he had never told a humorous story, his sense of humor was the most fascinating feature of his personal qualities.

He was the most exquisite humorist I have ever known in my life. His humor was always spontaneous, and that gave it a zest and elegance that the professional humorist never attains.

As a rule, the men who have become conspicuous in the country as humorists have excelled in nothing else. S. S. Cox, Proctor Knott, John P. Hale and others were humorists in Congress. When they arose to speak if they failed to be humorous they utterly failed, and they rarely strove to be anything but humorous. Such men often fail, for the professional humorist, however gifted, cannot always be at his best, and when not at his best he is grievously disappointing.

I remember Corwin, of Ohio, who was a great statesman as well as a great humorist, but whose humor predominated in his public speeches in Senate and House, warning a number of the younger Senators and Representatives on a social occasion when he had returned to Congress in his old age, against seeking to acquire the reputation of humorists. He said it was the mistake of his life. He loved it as did his hearers, but the temptation to be humorous was always uppermost, and while his speech on the Mexican War was the greatest ever delivered in the Senate, excepting Webster's reply to Hayne, he regretted that he was more known as a humorist than as a statesman.

His first great achievement in the House was delivered in 1840 in reply to General Crary, of Michigan, who had attacked General Harrison's military career. Corwin's reply in defense of Harrison is universally accepted as the most brilliant combination of humor and invective ever delivered in that body. The venerable John Quincy Adams a day or two after Corwin's speech, referred to Crary as "the late General Crary," and the justice of the remark from the "Old Man Eloquent" was accepted by all. Mr. Lincoln differed from the celebrated humorists of the country in the important fact that his humor was unstudied. He was not in any sense a professional humorist, but I have never in all my intercourse with public men, known one who was so apt in humorous illustration us Mr. Lincoln, and I have known him many times to silence controversy by a humorous story with pointed application to the issue.

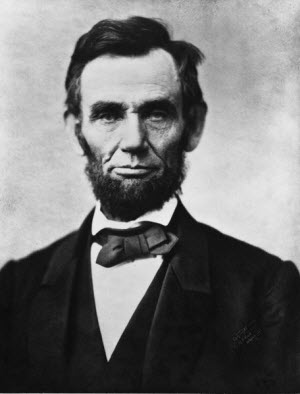

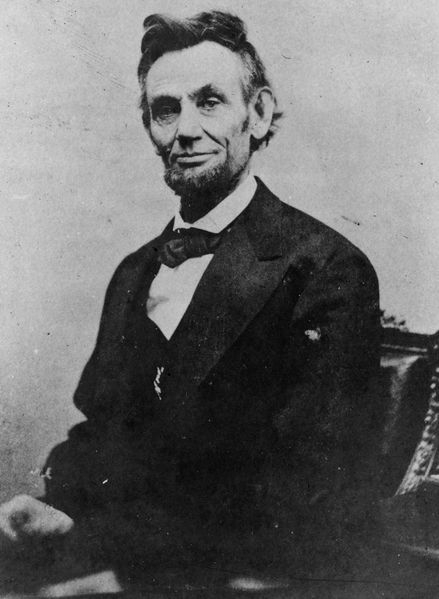

His face was the saddest in repose that I have ever seen among accomplished and intellectual men, and his sympathies for the people, for the untold thousands who were suffering bereavement from the war, often made him speak with his heart upon his sleeve, about the sorrows which shadowed the homes of the land and for which his heart was freely bleeding.

I have many times seen him discussing in the most serious and heartfelt manner the sorrows and bereavements of the country, and when it would seem as though the tension was so strained that the brittle cord of life must break, his face would suddenly brighten like the sun escaping from behind the cloud to throw its effulgence upon the earth, and he would tell an appropriate story, and much as his stories were enjoyed by his hearers none enjoyed them more than Mr. Lincoln himself.

I have often known him within the space of a few minutes to be transformed from the saddest face I have ever looked upon to one of the brightest and most mirthful. It was well known that he had his great fountain of humor as a safety valve; as an escape and entire relief from the fearful exactions his endless duties put upon him. In the gravest consultations of the cabinet where he was usually a listener rather than a speaker, he would often end dispute by telling a story and none misunderstood it; and often when he was pressed to give expression on particular subjects, and his always abundant caution was baffled, he many times ended the interview by a story that needed no elaboration.

I recall an interview with Mr. Lincoln at the White House in the spring of 1865, just before Lee retreated from Petersburg. It was well understood that the military power of the Confederacy was broken, and that the question of reconstruction would soon be upon us.

Colonel Forney and I had called upon the President simply to pay our respects, and while pleasantly chatting with him General Benjamin F. Butler entered. Forney was a great enthusiast, and had intense hatred of the Southern leaders who had hindered his advancement when Buchanan was elected President, and he was bubbling over with resentment against them. He introduced the subject to the President of the treatment to be awarded to the leaders of the rebellion when its powers should be confessedly broken, and he was earnest in demanding that Davis and other conspicuous leaders of the Confederacy should be tried, condemned and executed as traitors.

General Butler joined Colonel Forney in demanding that treason must be made odious by the execution of those who had wantonly plunged the country into civil war. Lincoln heard them patiently, as he usually heard all, and none could tell, however carefully they scanned his countenance what impression the appeal made upon him.

I said to General Butler that, as a lawyer pre-eminent in his profession, he must know that the leaders of a government that had beleaguered our capital for four years, and was openly recognized as a belligerent power not only by our government but by all the leading governments of the world, could not be held to answer to the law for the crime of treason.

Butler was vehement in declaring that the rebellious leaders must be tried and executed. Lincoln listened to the discussion for half an hour or more and finally ended it by telling the story of a common drunkard out in Illinois who had been induced by his friends time and again to join the temperance society, but had always broken away. He was finally gathered up again and given notice that if he violated his pledge once more they would abandon him as an utterly hopeless vagrant. He made an earnest struggle to maintain his promise, and finally he called for lemonade and said to the man who was preparing it: "Couldn't you put just a drop of the cratur in unbeknownst to me?"

After telling the story Lincoln simply added: "If these men could get away from the country unbeknownst to us, it might save a world of trouble." All understood precisely what Lincoln meant, although he had given expression in the most cautious manner possible and the controversy was ended.

Lincoln differed from professional humorists in the fact that he never knew when he was going to be humorous. It bubbled up on the most unexpected occasions, and often unsettled the most carefully studied arguments. I have many times been with him when he gave no sign of humor, and those who saw him under such conditions would naturally suppose that he was incapable of a humorous expression. At other times he would effervesce with humor and always of the most exquisite and impressive nature. His humor was never strained; his stories never stale, and even if old, the application he made of them gave them the freshness of originality.

I recall sitting beside him in the White House one day when a message was brought to him telling of the capture of several brigadier-generals and a number of horses somewhere out in Virginia. He read the dispatch and then in an apparently soliloquizing mood, said: "Sorry for the horses; I can make brigadier-generals."

There are many who believe that Mr. Lincoln loved to tell obscene or profane stories, but they do great injustice to one of the purest and best men I have ever known. His humor must be judged by the environment that aided in its creation.

As a prominent lawyer who traveled the circuit in Illinois, he was much in the company of his fellow lawyers, who spent their evenings in the rude taverns of what was then almost frontier life. The Western people thus thrown together with but limited sources of culture and enjoyment, logically cultivated the story teller, and Lincoln proved to be the most accomplished in that line of all the members of the Illinois bar. They had no private rooms for study, and the evenings were always spent in the common barroom of the tavern, where Western wit, often vulgar or profane, was freely indulged in, and the best of them at times told stories which were somewhat "broad;" but even while thus indulging in humor that would grate harshly upon severely refined hearers, they despised the vulgarian; none despised vulgarity more than Lincoln.

I have heard him tell at one time or another almost or quite all of the stories he told during his Presidential term, and there were very few of them which might not have been repeated in a parlor and none descended to obscene, vulgar or profane expressions. I have never known a man of purer instincts than Abraham Lincoln, and his appreciation of all that was beautiful and good was of the highest order.

It was fortunate for Mr. Lincoln that he frequently sought relief from the fearfully oppressive duties which bore so heavily upon him. He had immediately about him a circle of men with whom he could be "at home" in the White House any evening as he was with his old time friends on the Illinois circuit.

David Davis was one upon whom he most relied as an adviser, and Leonard Swett was probably one of his closest friends, while Ward Lamon, whom he made Marshal of the District of Columbia to have him by his side, was one with whom he felt entirely "at home." Davis was of a more sober order but loved Lincoln's humor, although utterly incapable of a humorous expression himself. Swett was ready with Lincoln to give and take in storyland, as was Lamon, and either of them, and sometimes all of them, often dropped in upon Lincoln and gave him an hour's diversion from his exacting cares. They knew that he needed it and they sought him for the purpose of diverting him from what they feared was an excessive strain.

His devotion to Lamon was beautiful. I well remember at Harrisburg on the night of February 22, 1861, when at a dinner given by Governor Curtin to Mr. Lincoln, then on his way to Washington, we decided, against the protest of Lincoln, that he must change his route to Washington and make the memorable midnight journey to the capital. It was thought to be best that but one man should accompany him, and he was asked to choose. There were present of his suite Colonel Sumner, afterwards one of the heroic generals of the war, Norman B. Judd, who was chairman of the Republican State Committee of Illinois, Colonel Lamon and others, and he promptly chose Colonel Lamon, who alone accompanied him on his journey from Harrisburg to Philadelphia and thence to Washington.

Before leaving the room Governor Curtin asked Colonel Lamon whether he was armed, and he answered by exhibiting a brace of fine pistols, a huge bowie knife, a black jack, and a pair of brass knuckles. Curtin answered: "You'll do," and they were started on their journey after all the telegraph wires had been cut. We awaited through what seemed almost an endless night, until the east was purpled with the coming of another day, when Colonel Scott, who had managed the whole scheme, reunited the wires and soon received from Colonel Lamon this dispatch: "Plums delivered nuts safely," which gave us the intensely gratifying information that Lincoln had arrived in Washington.

Of all the Presidents of the United States, and indeed of all the great statesmen who have made their indelible impress upon the policy of the Republic, Abraham Lincoln stands out single and alone in his individual qualities. He had little experience in statesmanship when he was called to the Presidency. He had only a few years of service in the State Legislature of Illinois, and a single term in Congress ending twelve years before he became President, but he had to grapple with the gravest problems ever presented to the statesmanship of the nation for solution, and he met each and all of them in turn with the most consistent mastery, and settled them so successfully that all have stood unquestioned until the present time, and are certain to endure while the Republic lives.

In this he surprised not only his own cabinet and the leaders of his party who had little confidence in him when he first became President, but equally surprised the country and the world.

He was patient, tireless and usually silent when great conflicts raged about him to solve the appalling problems which were presented at various stages of the war for determination, and when he reached his conclusion he was inexorable. The wrangles of faction and the jostling of ambition were compelled to bow when Lincoln had determined upon his line of duty.

He was much more than a statesman; he was one of the most sagacious politicians I have ever known, although he was entirely unschooled in the machinery by which political results are achieved. His judgment of men was next to unerring, and when results were to be attained he knew the men who should be assigned to the task, and he rarely made a mistake.

I remember one occasion when he summoned Colonel Forney and myself to confer on some political problem, he opened the conversation by saying: "You know that I never was much of a conniver; I don't know the methods of political management, and I can only trust to the wisdom of leaders to accomplish what is needed."

Lincoln's public acts are familiar to every schoolboy of the nation, but his personal attributes, which are so strangely distinguished from the attributes of other great men, are now the most interesting study of young and old throughout our land, and I can conceive of no more acceptable presentation to the public than a compilation of anecdotes and incidents pertaining to the life of the greatest of all our Presidents.

A.K. McClure

Abraham Lincoln | Events | People | Abraham Lincoln Quotes |

Quotations About Abraham Lincoln | Abraham Lincoln Photo Gallery | Abraham Lincoln Timeline |

Privacy Policy | About Us | Site News | Site Map |

Anecdotes and Stories About Abraham Lincoln